By Jo Nova

The winds of change are howling through electricity grids

Since 2022, AI -related firms have stormed the S&P 500 market — growing by $12 trillion dollars.

The IEA just posted a whole report dedicated to AI. The demand from data-centers is so large in some places it is already rivaling the kind of monster consumption we are used to seeing from aluminum smelters. There are six states in the United States where data centers already consume over 10% of the electricity supply. In Ireland, data centers swallow about 20% of the electricity.

Currently, a normal data center consumes the same amount of electricity as 100,000 houses. But the new gargantuan data centers under construction will consume 20 times as much — equivalent to adding 2 million homes to the grid.

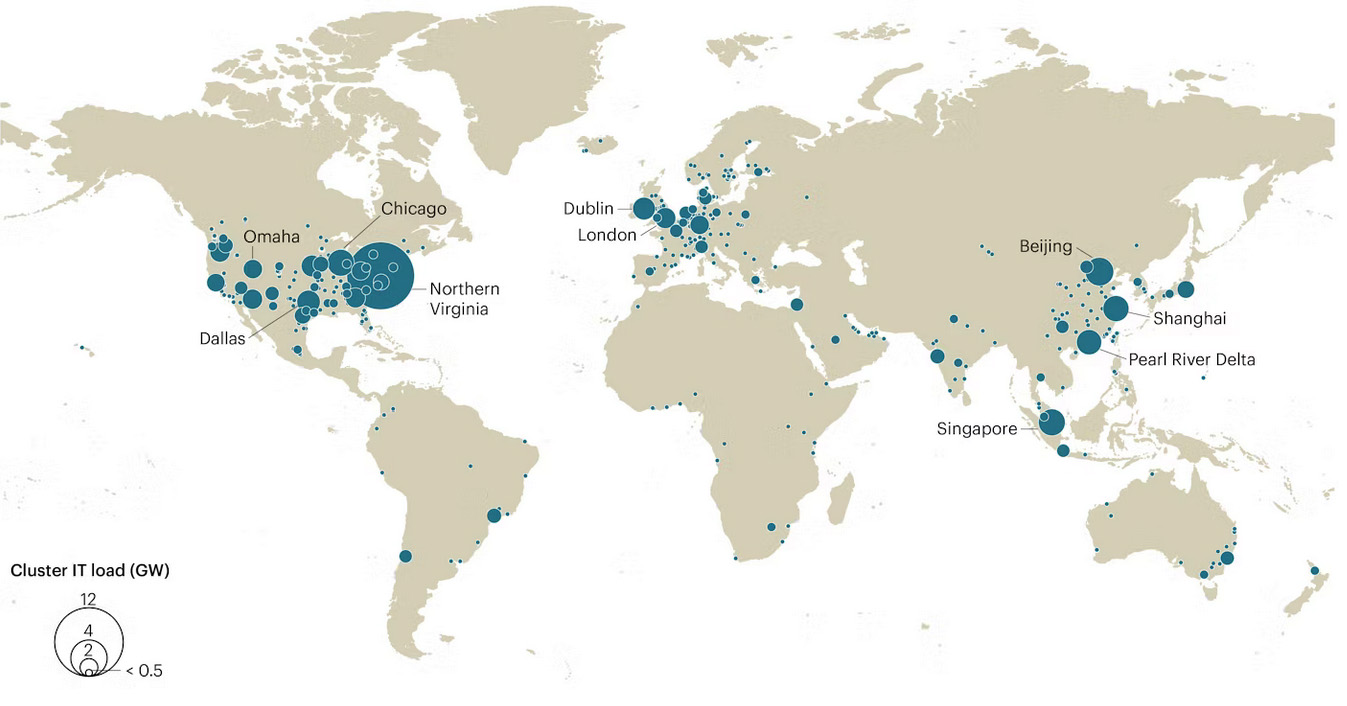

Data centers of the world are not spread evenly. In Virginia, the largest conglomeration of industrial data, their demand for power pulls in a quarter of the state’s electricity.

Australia is being left behind, because we won’t build coal plants in case we offend the UN, and we banned nuclear power as a fashion statement in 1998. The AI global race is on, but digital machines need reliable cheap electricity and lots of it.

Also not looking sparkling on the graph above — New Zealand, Norway, Sweden and Canada.

Sometime between now and 2030 (which is like ‘next week’) the world has to build a new network the size of Japan’s national grid — the fourth largest economy in the world.

Data centres accounted for around 1.5% of the world’s electricity consumption in 2024, or 415 terawatt-hours (TWh). The United States accounted for the largest share of global data centre electricity consumption in 2024 (45%), followed by China (25%) and Europe (15%). Globally, data centre electricity consumption has grown by around 12% per year since 2017, more than four times faster than the rate of total electricity consumption. AI-focused data centres can draw as much electricity as power-intensive factories such as aluminium smelters, but they are much more geographically concentrated. Nearly half of data centre capacity in the United States is in five regional clusters.

Data centre electricity consumption is set to more than double to around 945 TWh by 2030. This is slightly more than Japan’s total electricity consumption today.

There is no single factor driving up electricity demand more than AI at the moment:

In the United States, data centres account for nearly half of electricity demand growth between now and 2030. By the end of the decade, the country is set to consume more electricity for data centres than for the production of aluminium, steel, cement, chemicals and all other energy-intensive goods combined.

The IEA report, which was always a sop for “renewables” — suddenly isn’t that concerned about carbon emissions. This is an interesting shift. Almost like there is a sea-change in priorities of whoever it is that controls agencies like the IEA. Now it’s making excuses for industry…

“Concerns that AI could accelerate climate change appear overstated, as do expectations that AI alone will address the issue”

The widespread adoption of existing AI applications could lead to emissions reductions that are far larger than emissions from data centres – but also far smaller than what is needed to address climate change.

Just like private jets for billionaires, big new AI computers will save us from carbon emissions (maybe)

AI will find cost savings all over the place, but then again, if everyone has their own automated self-driving car, they won’t need to catch the bus will they? Oh the dilemma…?

AI applications in transport can improve efficiency and save costs, but they could also increase demand for personal mobility. AI applications are being used to manage traffic, optimise routes, predict maintenance needs and develop autonomous vehicles. The widespread adoption of AI applications across the transport sector could lead to energy savings equivalent to the energy used by 120 million cars. While autonomous vehicles operate more efficiently than conventional ones, they might also attract people away from public transport as costs fall and availability increases, leading to rebound effects.

In buildings, there is significant potential for AI-led optimisations to make heating and cooling systems more efficient and electricity use in buildings more flexible

Even the IEA admits we need affordable and reliable power

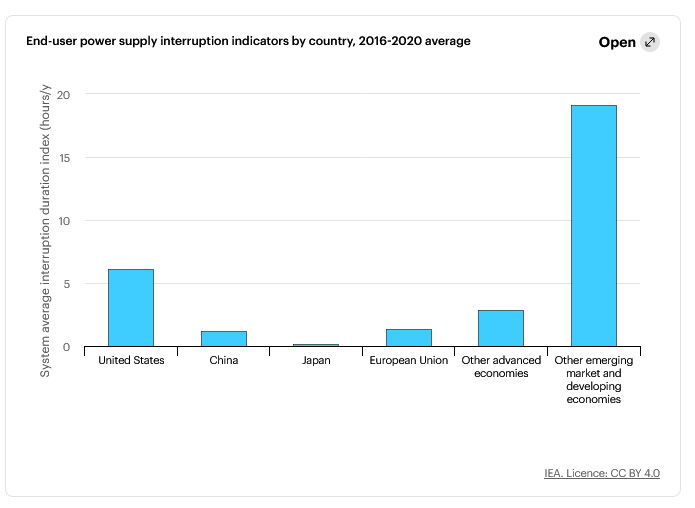

Countries with a record of reliable and affordable power will be best placed to unlock data centre growth, localise the computing power that is critical to homegrown AI development, and spur the IT industry more generally.

This graph with a microscopic font, compares how extensive those blackouts are around the world, with the First-World looking good (so far):

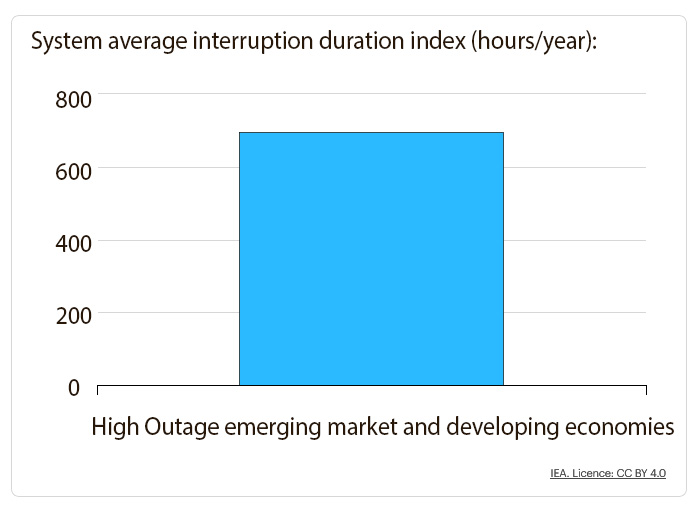

Beside that graph they have a very strange graph with microscopic fonts (which I expanded below) which has one solid square all by itself. This turns out to be the other emerging markets and developing economies they didn’t mention in the last graph.

The High Outage Country class of 2025 has more like 700 hours of average system interruption a year. It’s “off the charts” bad.

Tacitly, it suggests that the AI revolution won’t be moving to South Africa or Cuba.

Is there any industrial complex in the universe that works better on a part time random basis than it does on a predictable, reliable schedule?

History will show that countries with energy to spare will take over the world, and maybe the solar system.

REFERENCES